Data Model Layers and Jobs

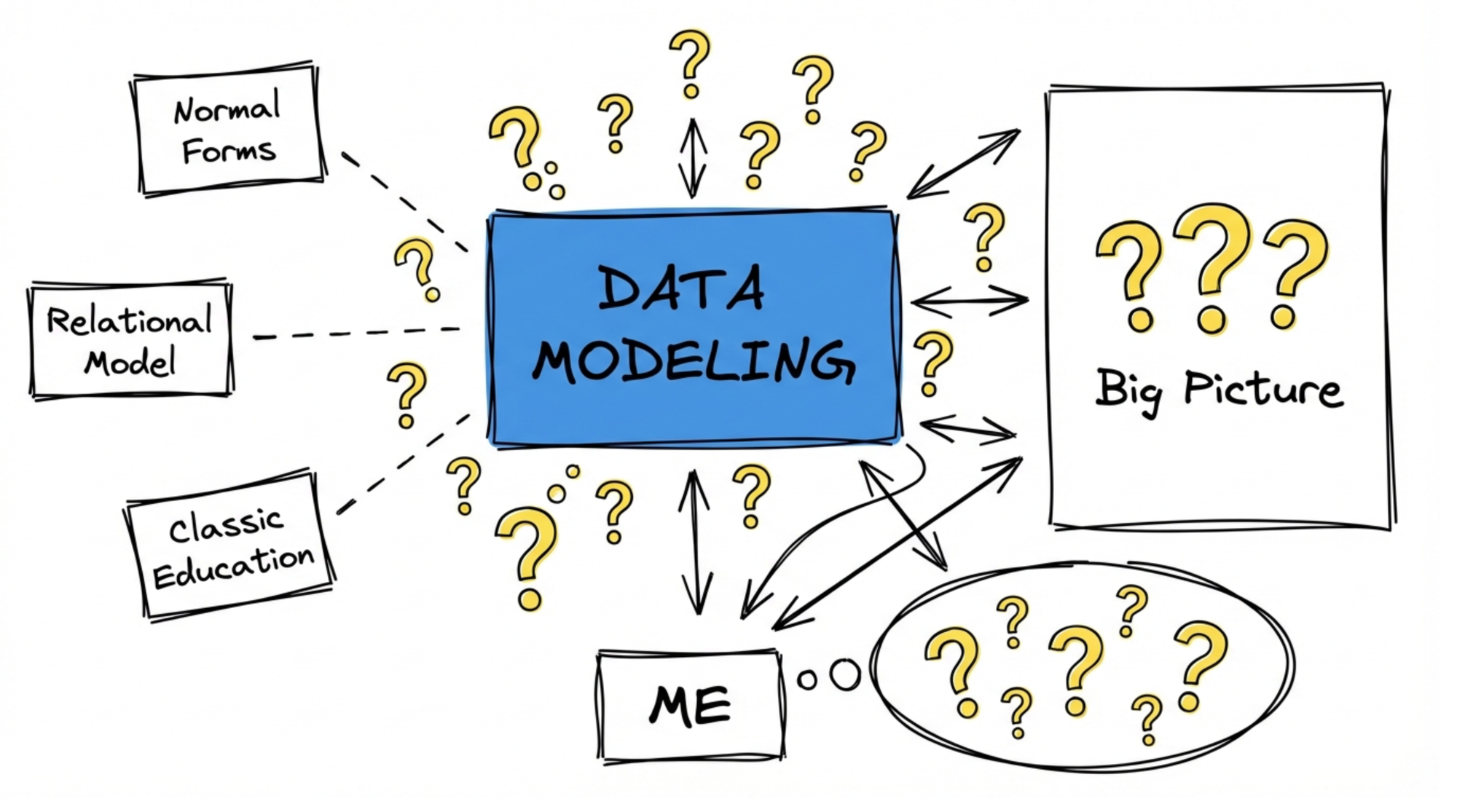

I had a hard time getting into data modeling.

When I started building my first models for e-commerce use cases, I kept asking the same question: how do we actually do this? What's a good structure? Unfortunately, the people I worked with didn't have a clue either. We had some classic education - we knew what a relational model was, we understood normal forms - but it always felt like these concepts were too primitive. They helped to some degree, but what I was missing was the big picture.

So I did what you do: I picked up books. On Amazon, I found the Kimball references. I thought the publication date was a mistake - 1980-something couldn't be right. There had to be something newer. There wasn't, so I got my first Kimball book. I learned about the star schema approach, fact tables, and dimensional tables. It made more sense, but it still wasn't the big picture I was looking for. Interestingly, I never came across Bi Inmon's work back then, which probably would have helped more with the architectural view. Bad Amazon search, I guess, or bad me.

This drove me a little crazy. I have a computer science background, and in CS you're taught to think in higher-level concepts. Object-oriented programming. Functional programming. Pure functions. You have frameworks that help you think through different approaches, understand how they differ, see where they shine, and where they struggle. I couldn't find the equivalent for data modeling.

Later, I talked to more experienced people, got better book recommendations, and finally gathered enough material to develop my own version of the big picture. And here's the thing I realized: this seems to be pretty common in data modeling. When you talk to practitioners, yes, there's some overlap - but everyone has their own flavor. My usual joke when clients ask if my data models follow a standard approach: if you asked 10 data modelers to build a model for your case, you'd see maybe 30-40% overlap. The rest is variation. Far more than you'd expect from a mature discipline.

So when I stumbled across a LinkedIn post about layers a few years back, something clicked.

Layers - the organizing principle most of us adapted

The LinkedIn post - and I'm sorry I can't remember who wrote it - presented layers as a way to shape data until it's ready for a specific use case. Think of it like filtering water through different materials. Data flows through each layer, getting refined along the way. Not a perfect analogy since you don't end up with pure data at the end - it's still messy - but you get the idea.

The concept stuck with me. And once you start looking, you see layers everywhere.

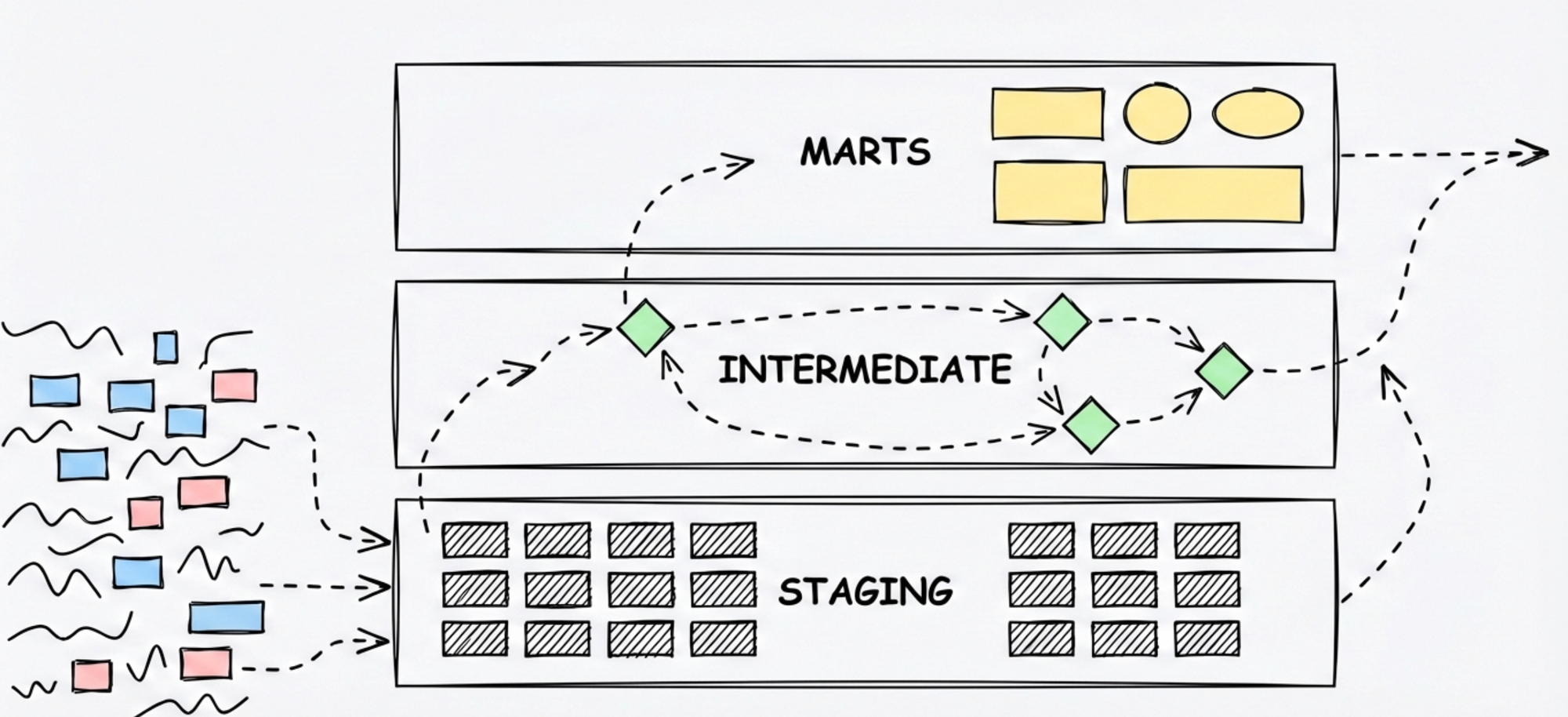

When dbt became popular, they established their own layer approach: staging, intermediate, and marts. Then Databricks brought us the medallion architecture - bronze, silver, gold. The medallion version is particularly popular, and I think I know why: it's sales compatible. Salespeople love it because it fits perfectly into a story. "You start with messy data in bronze, refine it to silver, and end up with gold." Gold sounds great. Who doesn't want gold?

But here's the thing - whether it's dbt's three layers or medallion's three layers, it's still just three loosely defined buckets. And when you ask people to explain what actually happens in each layer, the answers start to diverge.

What layers actually do for you

At their simplest, layers act like folders. Directories. They structure your data model into distinctive areas.

Take dbt's approach. Staging is the welcome mat - you decide what raw data to pull in and apply some basic transformations. Intermediate is where stuff happens, usually business rules, though what exactly happens there is often hard to pin down. Marts is where you shape things for your end application - maybe a star schema for your BI tool, with fact tables and dimensions.

This structure helps in practical ways.

When your data model grows and you need to add a new source - say, someone introduces a new marketing tool - you know where to start. You don't jump straight to creating a fact table. You begin in staging.

When you notice repeating patterns across your reports - the same calculation happening in three different fact tables - you can centralize it. Maybe that logic belongs in intermediate, so you're not repeating yourself.

And there's cost optimization. Raw data from tools like Google Analytics 4 is notoriously wide. Dozens of fields you'll never use. Every query against that raw schema costs money. A staging layer can slim this down - you decide what actually matters for analysis and filter out the rest. For anyone querying GA4 raw data directly, building even a simple staging model is usually the first step toward controlling costs.

So layers make sense. They give structure, they enforce some discipline, they help teams orient themselves in a growing codebase.

The problem is what happens when you look closer.

Where layers fall apart

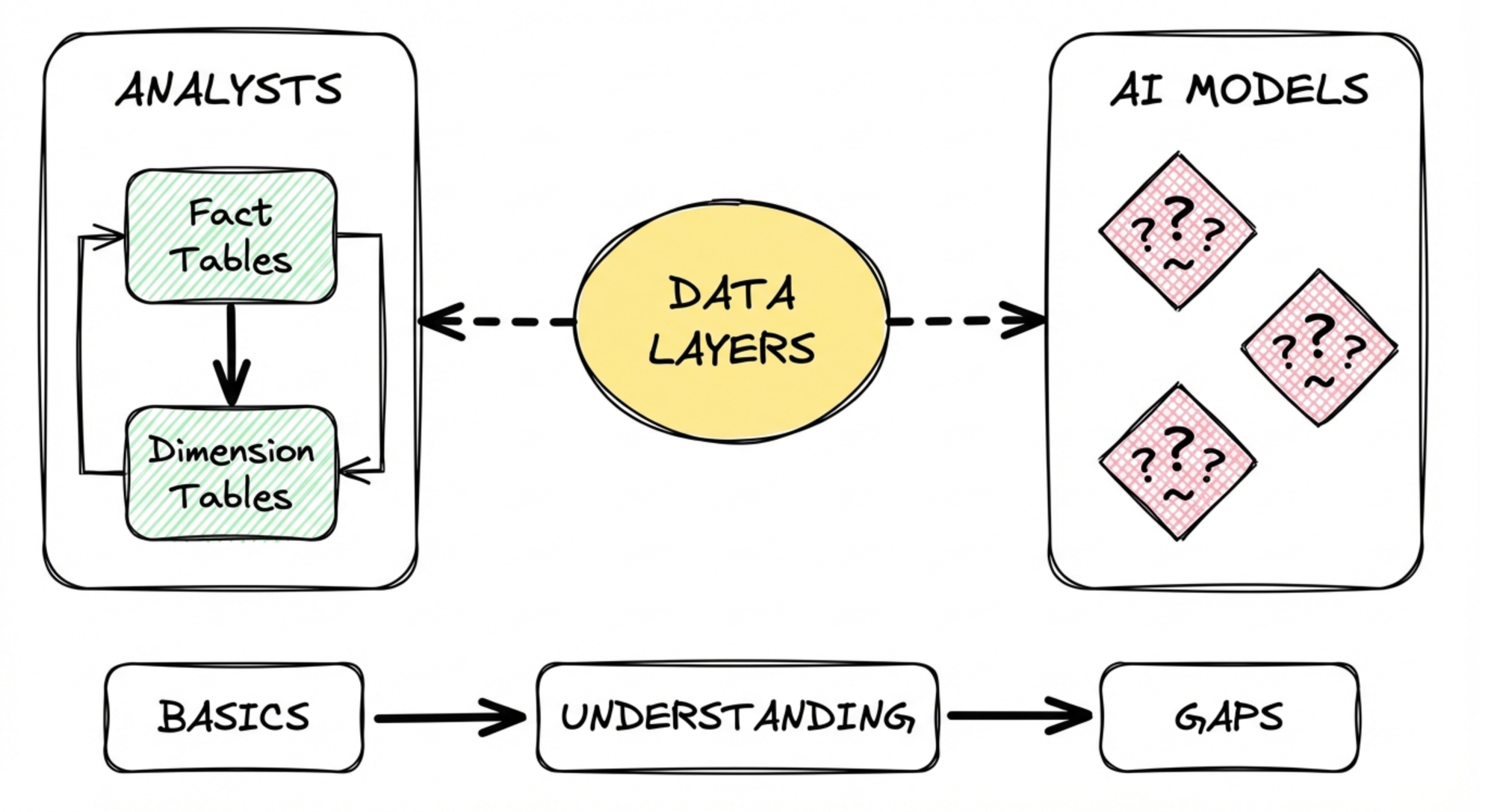

In the last year, I spent a lot of time teaching data modeling to two very different audiences: analysts who hadn't worked with data models before, and Gen AI models. Both experiences exposed the same weakness in how we talk about layers.

The analysts picked up the basics fast. Fact tables and dimension tables clicked immediately - it maps to how they already think. Measures and dimensional values, that's their world. Wide pre-joined tables? They get it. Precalculated fields make their BI work easier.

But then you try to explain the staging layer, and things get fuzzy.

"We standardize stuff there."

"What do we standardize?"

"Well, we align timestamps. Everything gets the same format."

They can follow that. But then they ask: "Why do we do it there? Why not just do it on the fact table?" And you say, well, it's good practice to centralize it because we might use it somewhere else. And they look at your model and point out: "But we don't use this timestamp anywhere else. It's only in this one fact table."

The deeper you go into the underlying layers, the harder it gets to explain why things are where they are.

Teaching Gen AI models made this painfully clear. I've spent enough time with agentic approaches to know how to break down work - how to plan, how to chunk tasks. But even with all that applied, the first data models I generated were not good. I'd look at what ended up in staging and think: no, that doesn't belong there. It didn't fit my flavor.

And that's the problem. Flavor.

I tried to write context for the models - clear definitions of what should happen in each layer. This is usually what makes or breaks Gen AI output. But I couldn't write a staging definition that worked everywhere. Because it depends.

Here's what I mean. A staging layer can do two very different jobs.

A light staging layer does basic transformation. You establish naming conventions - all timestamps become ts, you normalize types, you standardize wording. Simple stuff.

A strong staging layer does something heavier. In one project, I work with 20-30 different advertising platforms. The staging layer there acts like a data contract. We define exactly how campaign data should look like - these identifiers, this metadata, these measures - and we map every source into that shape. Naming conventions, field mapping, all of it happens there.

But does it have to happen in staging? No. You could do a light staging layer and then add a separate mapping layer. Both approaches are valid. There's no decision framework that tells you which to choose.

This is the core issue. Layers are loosely coupled. They're an organizing principle, not a strongly typed system. You can't write clear rules for when something belongs in staging versus intermediate versus somewhere else. Which is exactly why, when you look at how different teams implement the same layer concepts, you find wildly different results wearing the same labels.

Jobs as an alternative framing

Before I go further, a caveat: what follows is still a thought experiment. I've been tinkering with this for three or four months. It's not a finished framework. But it's been useful enough that I think it's worth sharing - and I'd love to hear from others who are exploring similar ideas.

If you've followed my work, what comes next probably won't surprise you. I have a product background, and sometimes you come across a concept that works so well in one area that you start applying it everywhere. For me, that's Jobs to be Done.

JTBD was the framework that finally explained product work to me. And if you dig into it - I highly recommend everything Bob Moesta has written - you realize it's not really a product principle. It's a general principle you can apply to many domains.

So when I went back to the drawing board with my Gen AI data modeling experiments, trying to figure out what context to provide, I didn't consciously think "I should frame these transformations as jobs." I just started writing definitions for what each transformation should accomplish. And when I stepped back and looked at what I'd created, I realized: I'd been defining jobs the whole time. It's my atomic unit. Everything falls back into it.

From "where does it live" to "what does it do"

The basic principle of Jobs to be Done is a change in perspective. Usually, we start from the asset - the product, the data model - and define everything from there. JTBD flips it. You start from the progress you want to achieve and work backwards.

In data modeling terms: instead of asking "which layer does this transformation belong in?", you ask "what job does this transformation need to accomplish?"

The difference sounds subtle, but it changes how you communicate about your data model.

Take timestamps. In a layers framing, you might say: "We handle timestamp normalization in staging." Okay, but why staging? And what exactly happens there?

In a jobs framing, you define a format alignment job. This job takes timestamps in whatever form they arrive - proper datetime formats, exotic string formats that need custom regex, Unix epochs, whatever - and normalizes them into one standard type that your database handles well. You apply this job early because you don't want to think about timestamp formats ever again downstream.

When you show this to someone, they immediately understand. "Oh, we always align timestamps like this." There's no ambiguity about what's happening or why.

Or take a heavier example: the advertising platforms I mentioned earlier. Instead of saying "we do mapping in staging" or debating whether mapping deserves its own layer, you define a data contract job. This job takes source data from any advertising platform and maps it into a standardized shape - these identifiers, this metadata, these measures. The job definition specifies what the output looks like, what validation happens, how edge cases get handled.

The job doesn't care which folder it lives in. It cares about the progress it delivers.

Here's a practical takeaway, even if you don't adopt this framing fully: take each layer in your current data model and try to describe what it actually does in six sentences. Not generic descriptions like "business logic happens here." Specific descriptions of what progress that layer delivers. If you can do that clearly, you've essentially defined the jobs - you just haven't called them that yet.

Light jobs, heavy jobs, and chaining

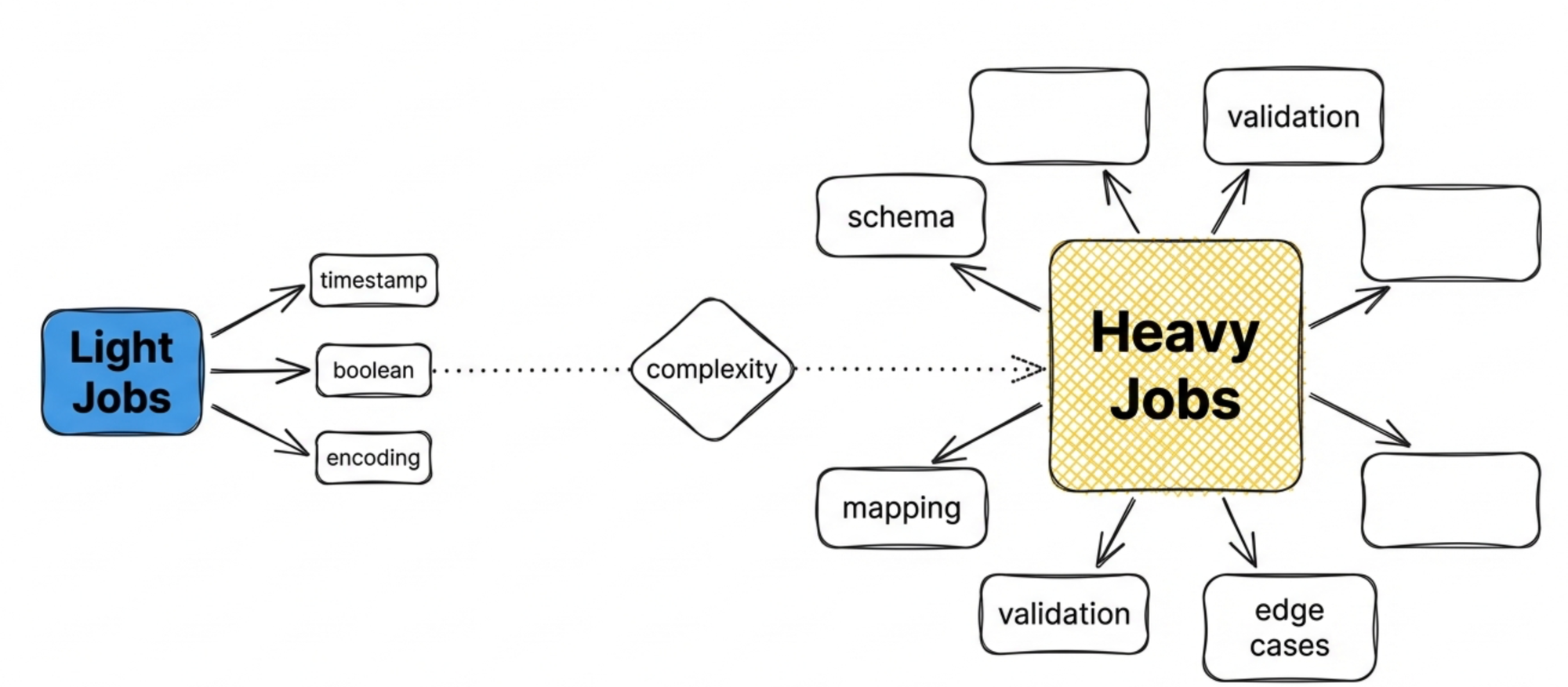

Not all jobs are the same size.

The timestamp alignment job is light. It does one thing, does it consistently, and you're done. Same for other formatting primitives - standardizing boolean representations, normalizing currency codes, cleaning up string encodings.

A data contract/mapping job is heavy. You're defining expected schemas, mapping multiple sources into a canonical shape, handling edge cases, validating outputs. It's a lot more work and a lot more complexity.

And here's where it gets interesting: light jobs often become components inside heavy jobs.

That timestamp alignment job? It's probably a primitive that lives inside your data contract job. You're not going to define timestamp handling separately for every source mapping - you use the primitive. Same with other formatting jobs. They become building blocks.

This creates a natural hierarchy. You have primitive jobs that handle atomic transformations. You have combining jobs that orchestrate primitives into something more substantial. And you have high-level jobs that deliver complete, usable outputs.

The challenge is that this doesn't map cleanly to how most data model infrastructure works today.

In dbt, the closest analog to primitive jobs would be macros. And I've used macros this way - packaging up reusable transformation logic. But macros have problems. Jinja templating makes them hard to read. I've worked with macros where the original author understood them perfectly, but nobody else could parse what was happening. They're a weird construct that pushes against what the platform wants to do.

So there's tension here. The jobs framing makes conceptual sense - you can see the hierarchy, you can explain it clearly - but the tooling doesn't natively support thinking this way.

The challenges (order, scale, early days)

I want to be honest about what's still unresolved.

Layers give you something for free: order. Staging happens first, then intermediate, then marts. When you need to work on foundational stuff, you know to look in staging. When you're building outputs, you're in marts. The sequence is baked into the structure.

Jobs don't give you that automatically.

Yes, some jobs are naturally earlier - format alignment happens before you build entities. But the job type itself doesn't tell you where it sits in the sequence. You have to solve for order separately.

There are options. You could use naming conventions - prefix early jobs with 1_ or base_, later jobs with 2_. You could organize by job type and accept that order is implicit. In my current setup, I've landed on three high-level jobs - source mapping, entities, analytics - and the flow between them is clear enough that order takes care of itself. But I don't have a universal answer here. It's too early.

Then there's scale. I mentioned light jobs and heavy jobs, but the spectrum is wide. A timestamp alignment job is trivial. A full attribution modeling job - handling multiple touch points, different attribution windows, various models for different teams - that's substantial. How do you organize a codebase where jobs range from five lines to five hundred? I'm still figuring that out.

And the honest truth is: I've only been working with this framing for some months. I'm using it in my personal data stack. I've seen it work for certain use cases - source mapping emerged as a clear job type almost immediately, and I'd already been thinking in terms of entity models and analytical outputs. But it hasn't faced enough reality yet.

Every model has to face reality at some point. That's when you learn what actually works and what looked good on paper but falls apart under pressure. I'm not there yet with this. What I can say is that the framing has been useful enough to share - and I'm curious whether others have been tinkering with similar ideas.

My practical experiment

About two months ago, when the dbt acquisition news hit and people started asking what a post-dbt world might look like, I decided to take the question seriously. Not because I think dbt is going away tomorrow, but because the question itself is interesting: if you started from scratch, what would you build differently?

dbt is a transformation orchestrator. It's agnostic - it doesn't care what SQL you run. That flexibility is a feature, but it also means dbt never enforced a strong opinion about what a data model should look like. Which is how you end up with those 600 to 1,000 model setups that nobody can navigate.

I wanted to try the opposite. Start with a strong opinion about what the output data model should be, and let everything else follow from that.

The principle I started with: fewer transformations are better. Every transformation and materialization introduces risk. The best data quality you can have is when you run no transformations at all - you just use the source data as-is. Obviously that's not realistic, but the principle holds. The fewer transformations you apply, the less risk you introduce.

So I built myself a stack. I removed dbt entirely and defined everything using Pydantic models. And what emerged was three high-level jobs.

Three high-level jobs: source mapping, entities, analytics

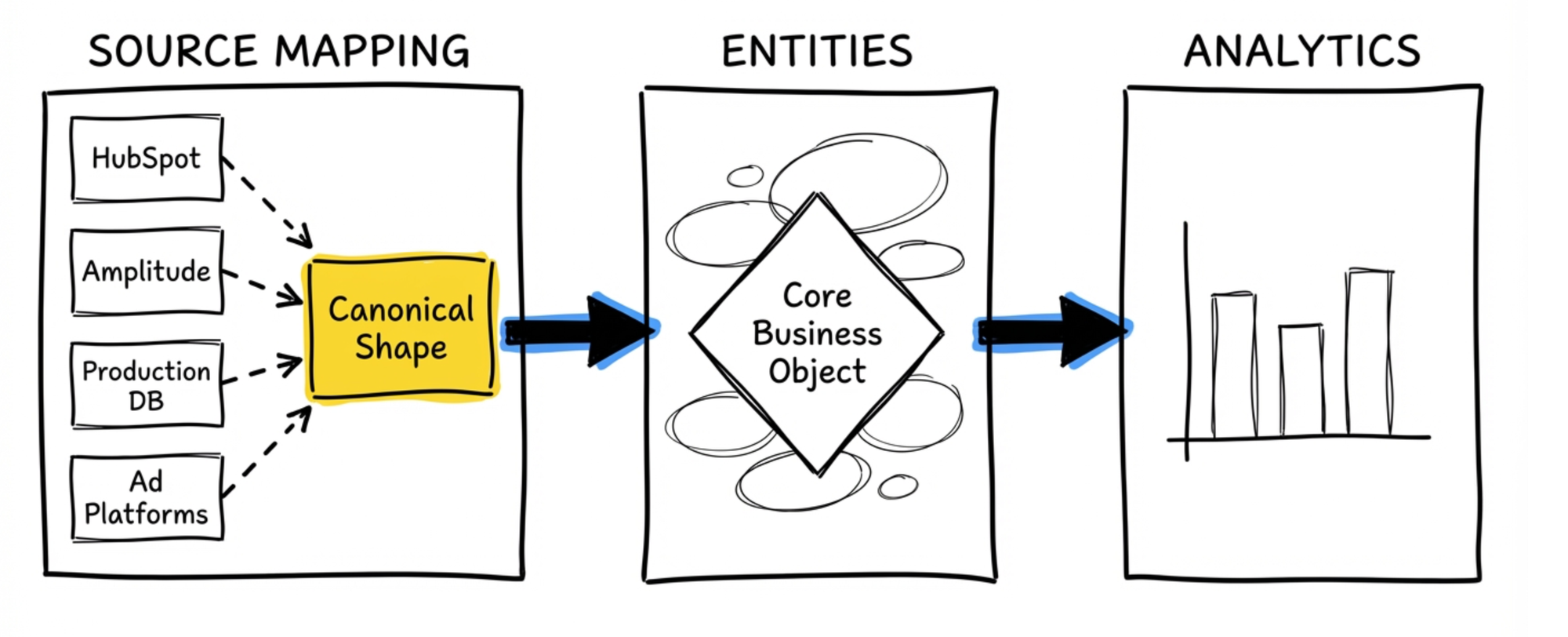

The first job is source mapping. This is the data contract work I described earlier. You have data coming from different places - HubSpot, Amplitude, your production database, advertising platforms - and you need to map it into a canonical shape. The source mapping job defines what that shape looks like and handles the translation from each source.

The second job is entity definition. This is where I land on what the core business objects actually are. In my case, since I work mostly with marketing and product use cases, the dominant entity is the account. Accounts are the things that bring money to your company. Accounts are what you analyze when you look at revenue performance. Everything else orbits around that.

I build my entity models to be very close to the business. And I consolidate aggressively. Where a traditional dimensional model might give you 30 or 40 tables, I aim for five or six strong entities. Denormalized, yes - but deliberately so. Each entity should be a solid, resilient representation of something the business actually cares about.

The third job is analytical definition. This is where you take your entities and shape them for specific analytical use cases. If you're familiar with the Maxim's entity model approach (https://preset.io/blog/introducing-entity-centric-data-modeling-for-analytics/), this is similar territory. You're deriving analytical datasets from your core entities - adding retention windows, building in the dimensions you need, preparing the data for the questions people actually ask.

What I found interesting: when you work with Pydantic to define all this, you naturally start building primitives. Timestamp handling, field validation, common transformations - these become reusable components that the higher-level jobs consume. The hierarchy I described earlier - primitive jobs feeding into heavier jobs - emerged organically from the structure.

The source mapping job wasn't there on day one. It emerged quickly once I started connecting multiple data sources. The analytical model concept I'd already been working with. The entity-centric approach has been my bias for years. So the three jobs aren't arbitrary - they're what fell out of trying to build something coherent.

What's still open

I've been using this approach for three or four months now. It's working for my personal data stack, and it's been useful when thinking through client problems. But that's not enough time to know what breaks.

The source mapping job proved itself quickly - as soon as you have multiple sources feeding the same entity, you need it. The entity-centric approach I've believed in for years, so that wasn't new. The analytical layer was already how I thought about outputs. But the whole system together? It hasn't faced enough reality yet.

Some specific things I'm still uncertain about:

How does this scale with a team? I've been the only one working in this stack. What happens when three people need to collaborate? Do the job definitions stay clear or do they drift into the same flavor problem that layers have?

Is three the right number of high-level jobs? It's what emerged for my use cases, but that doesn't mean it's universal. Maybe some domains need four. Maybe two would be enough for simpler setups.

I am pretty close to Data Kitchen's FITT architecture, but how can I get better at testing as they propose it as a core requirement (https://datakitchen.io/fitt-data-architecture/).

How do you handle jobs that don't fit cleanly? I mentioned attribution as a business rules job - but attribution touches source mapping, entity enrichment, and analytical outputs. Where does it actually live? I have a first answer for my setup, but I'm not confident it generalizes.

And honestly, is this actually better than well-defined layers, or just different?

Here's what I'd suggest if any of this resonates: take your current data model and try to describe each layer in six sentences. Not generic descriptions. Specific statements about what progress that layer delivers, what jobs it accomplishes. If you can do that clearly, you've already done the hard work - whether you call them layers or jobs doesn't matter much.

And if you've been tinkering with similar ideas - different ways to think about data model structure, alternatives to the layer paradigm, experiments with Pydantic or other approaches - I'd love to hear about it. This is early. The more people poking at the problem, the better.

Join the newsletter

Get bi-weekly insights on analytics, event data, and metric frameworks.