Design-driven Analytics

The symptoms aren't the problem

When I talk to people about their data challenges, we usually get to the pain points pretty quickly.

"We have a real issue with data quality. It's just not good enough, and we're not making progress."

Then there's the trust problem. "People don't trust our data." Sometimes this comes right after they've fixed the quality issues - which makes it even more frustrating. You fix the thing, and people still don't believe in it.

And then you get to literacy. "I think our real problem is that the company doesn't know how to work with data. We have all this stuff, but nobody actually uses it properly."

There's a whole collection of these. Data quality. Data trust. Data literacy. Data adoption. Each one gets positioned as the reason why data isn't working.

My answer to all of this is usually the same: I think you have a design problem.

Short break:

I am running my final free workshop this year about building a roadmap for a better product and growth analytics roadmap. How can you turn your current setup into something that shows you with few metrics if your product is converting new users into regular and happy users:

What I mean is that the data setup itself has a root issue. It was designed with too many flaws from the start. The quality issues, the trust issues, the adoption issues - these are symptoms. They're what you feel. But they're not the cause.

The cause is that someone built the whole thing pointing in the wrong direction.

Most data setups start with a very generic goal. It usually sounds something like this:

"We have so much data from all these different systems. We should use it to create better products. Or improve our marketing. Or make our operations more efficient."

There are two buckets here. On one side, there's all the data you have or could have - the potential. On the other side, there's all the things you do that could be done better - the opportunity.

And there are stories that connect these two worlds. Factory optimization after the war. Tech companies that seem to have figured it out. Some of these stories are true. There are definitely companies that found patterns in their data and used them to become more effective, to focus their resources better.

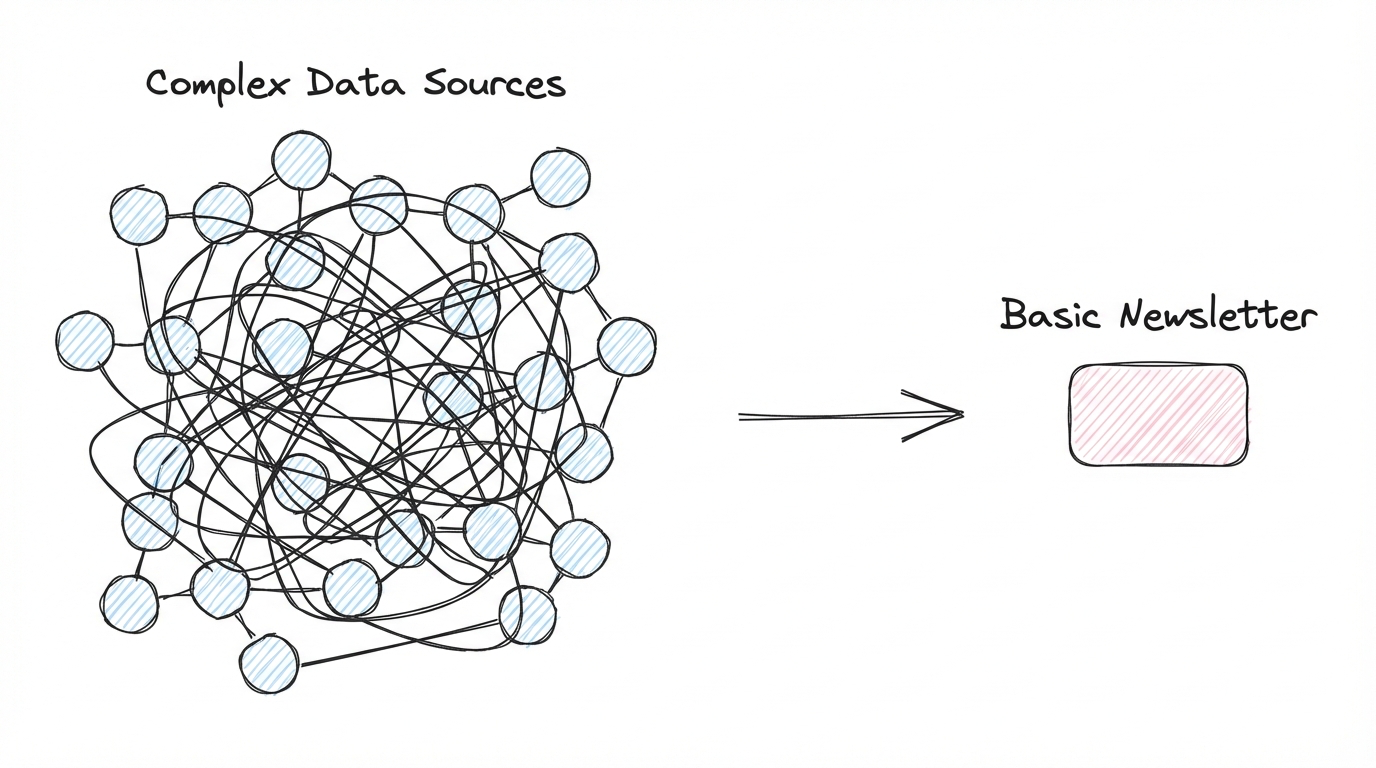

But here's the thing: the bridge between these two worlds is really hard to build. And most data projects don't even try to build it. They just build the left side.

"Let's collect everything. Revenue data - pipe it in. Ad platform data - pipe it in. Web tracking - well, let's just track all pages, all button clicks, everything. Then we bring it together and figure out how to support the business."

It doesn't work. Because it starts on the wrong side of things.

The logic feels reasonable. You don't know exactly what you'll need, so you collect broadly. You build the infrastructure first. Then you connect it to the business later.

But "later" has a way of never arriving. Or when it does, you realize the data you collected doesn't actually map to the decisions you need to make.

You have pageviews, but you can't tell which users are getting value from the product. You have button clicks, but you can't connect them to revenue. You have data from five systems, but the identifiers don't match up.

The bridge between data and operations was never designed. It was just assumed it would appear once enough data was in place.

It doesn't.

Two ways to fail

So if starting from data doesn't work, what does?

Before I get to that, I want to show you both extremes. Because it's not just the data-first approach that fails. The opposite fails too.

Customer data platforms are a perfect example of the data-first trap.

They had their peak maybe five to seven years ago, when they were one of the big new things. The promise was powerful but vague - finally, we can do something magic with all our customer data. What that magic actually meant was never quite clear. But the market is still around. I still do CDP projects.

The project always starts the same way. You identify all the places where customer data lives. One CRM. Maybe two. Actually, three. Then there's the email marketing tool - customer data there too. Web tracking, billing system, support tickets. It's everywhere.

So you start bringing it together. And then you discover all the nasty bits.

The data doesn't get along. Different systems, different structures. Identifiers are a mess - same customer shows up five different ways. You need an identity graph now. That's a project in itself. Data quality varies wildly across sources. One customer has twenty address entries, all slightly different. Which one do you pick? That needs rules. The rules need exceptions. The exceptions need documentation.

You can keep a small team busy for a year with this. Easily. Always improving, enhancing, adding another source, fixing another edge case. There's always one more thing to clean up before it's ready.

And the work feels important. It is important, in a way. You're building foundations. You're creating a single source of truth. These are real things that matter.

But here's what's missing: none of this has been connected to any actual business process yet.

Then finally, after all that, you connect it to something.

You use it to send newsletters.

The thing is - you were already sending newsletters before. The customer data platform didn't unlock that. It just made it more expensive.

I don't think you need to be deep into math to see that spending a year of engineering time to send newsletters is not a great return on investment.

The platform was built without operations in mind. The design started on the wrong side.

Now let's look at the opposite extreme.

When you work with young startups - especially ones with a very active, very smart growth team - you see a completely different approach. These teams are hardcore operational. They run multiple initiatives at the same time. In a six-week period, they might test three or four different ways to get more users into the product, improve stickiness, maybe add referral mechanics.

Two or three people running two or three bigger operations each. Content initiatives, podcasts, paid campaigns, partnership experiments. High energy, high speed.

And each initiative builds its own data setup.

How much data they collect depends on the initiative and the person running it. Some do more, some do less. Some are comfortable building out tracking and dashboards, others less so. But in the end, every operation has its own little data world that supports it.

Here's the thing: this actually works. Often it works really well. I've seen these setups deliver serious results. Fast feedback loops, quick iteration, real growth.

So what kills it?

At some point, the initial initiatives start to hit diminishing returns. The obvious wins are captured. And someone says: maybe we should align things. Bring it all together. Because right now, we're probably wasting time and money running these things in parallel. If we consolidate, we might see which initiatives actually matter. We might find patterns across them. We could be more effective.

So they start to build a unified data setup.

And that's when they realize they have twenty different data structures. Built by different people, for different purposes, with different assumptions. Identifiers don't match. Definitions don't match. Nothing was designed to connect.

Now you're on the opposite side of the problem. You have highly energized operations, but no foundations underneath. You're trying to build the bridge while the trains are already running.

Sometimes it works. Often it doesn't. Either way, it costs enormous energy and overhead. You're paying for the missing design work - just paying later, with interest.

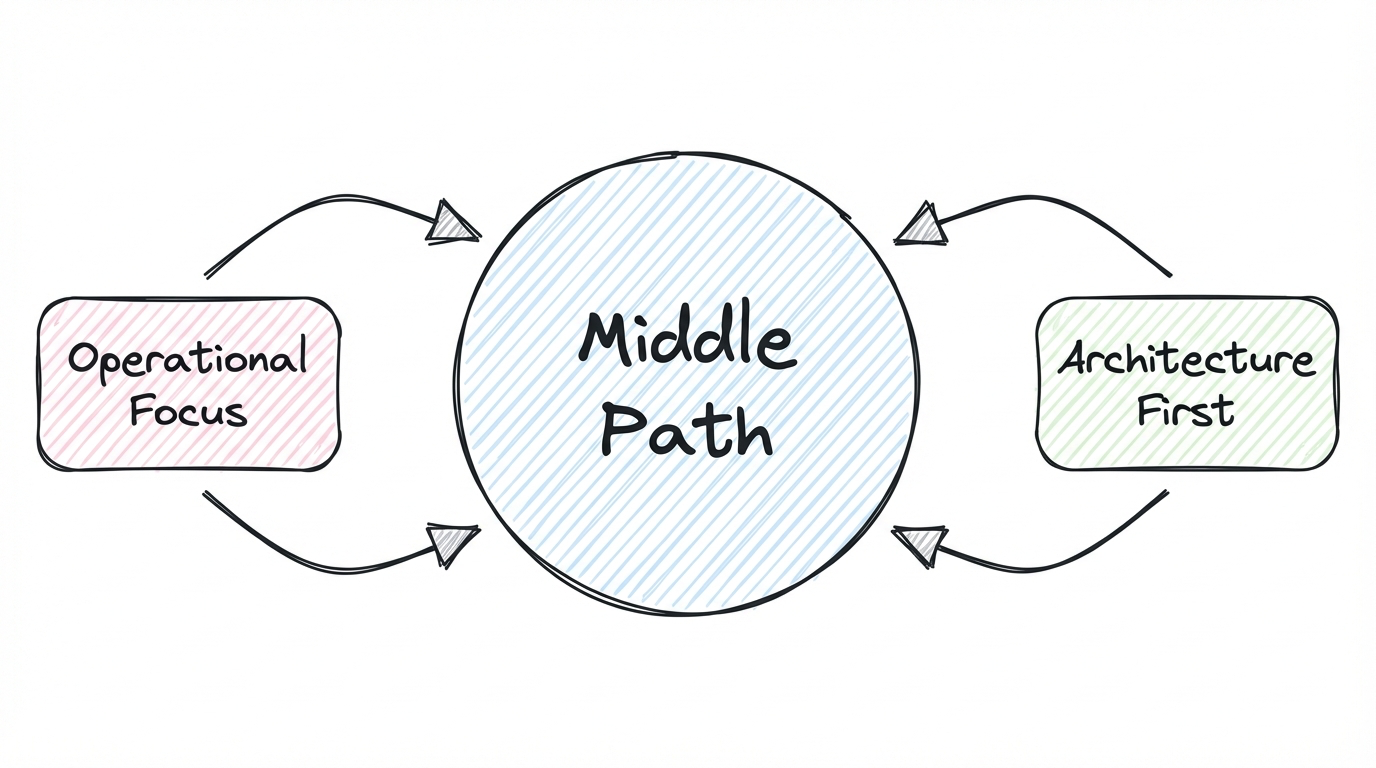

Both approaches fail for the same reason.

Data-first gives you foundations without operations. You build infrastructure that never connects to the business.

Operations-first gives you operations without foundations. You build momentum that can't be consolidated.

Neither one designs the connection from the start. The bridge between data and operations is just assumed to appear at some point. It doesn't.

The middle path

Now here's where I have to be honest.

What I'm about to present is not some mind-blowing simple model that magically brings these two extremes together. I don't have all the answers yet. There is still much I need to work through.

But I do think there's something in the middle. And I think we should spend more time there instead of defaulting to one of the extremes.

The middle path is a combination of both approaches. Not one, then the other. Both at the same time, from the start.

Every initiative you run needs two things:

First, a clear operational focus. You have to identify a specific process within the company - something where improvement would have a significant impact. Not "better marketing" but a specific channel. Not "improve the product" but a specific area, a specific user journey, a jobs to be done.

Second, a fundamental architecture that can scale. You need a data model that doesn't collapse under its own weight as you add more use cases. Something that keeps complexity at bay while the scope grows.

Most projects only do one. Build the infrastructure first, connect to operations later. Or run the operations first, worry about foundations later.

Design-driven analytics means you do both in parallel. The operational use case shapes the data model. The data model is designed to support more than just this one use case.

The operational side means picking a candidate. A specific part of the business that you want to support with data.

This could be a specific marketing channel. A specific area within the product. A particular stage in the customer journey. An onboarding flow. A retention mechanism. A sales handoff process.

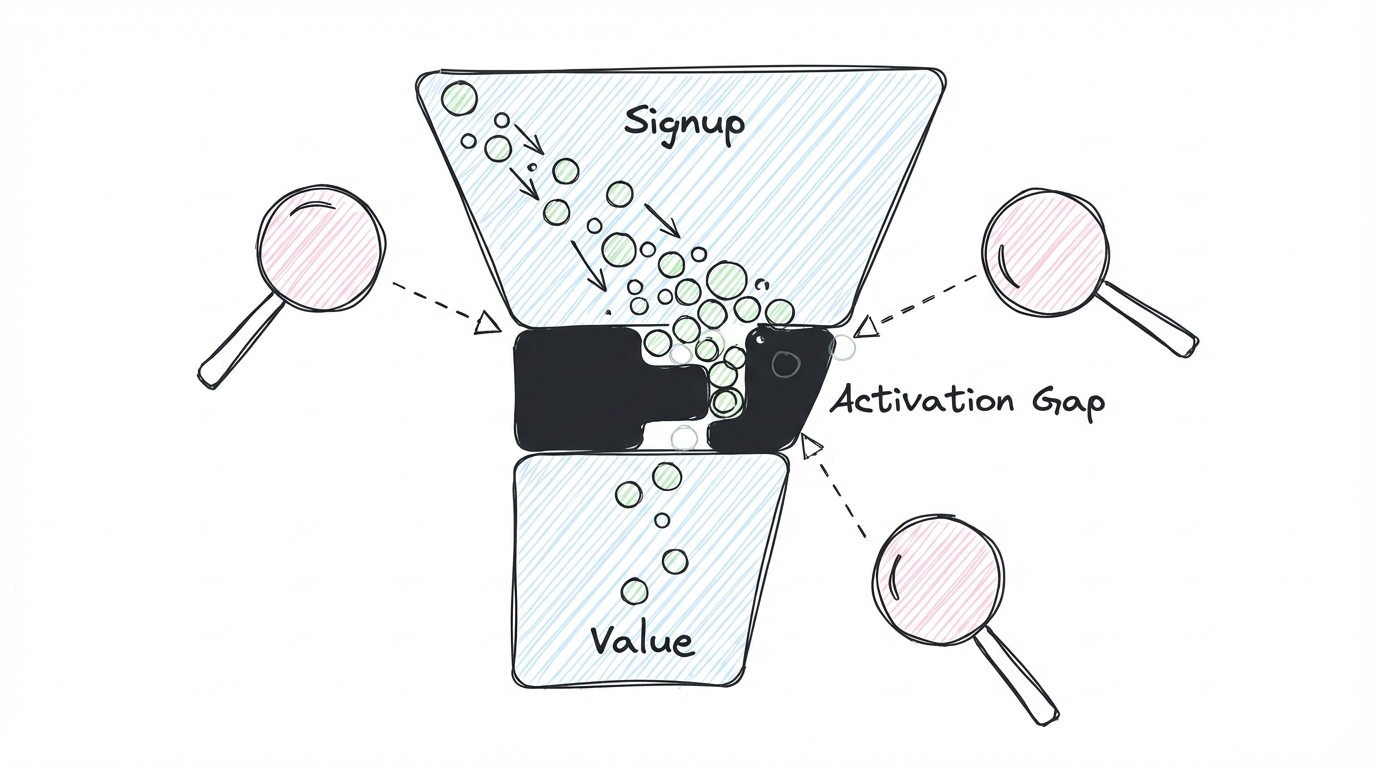

My personal favorite is user activation - it's still the biggest gap I see where companies are missing opportunities. Most teams track signups and they track active users, but the space in between is a black box. What happens between "created account" and "getting real value"? That's where you lose people. And that's where supporting the operation with good data can have an outsized impact.

The point is: it has to be specific. And it has to be something where improvement would actually move the needle. Not "better marketing" but a specific channel. Not "improve the product" but a specific user journey you can actually trace and measure.

This is already a challenge. How do you identify these high-impact operations?

I have some ideas that have worked for me. Look for operations where the team is already motivated but flying blind. Look for places where people are making decisions on gut feel because the data isn't there. Look for processes that touch revenue directly - acquisition, conversion, expansion, retention. Look for the thing that, if it improved by 20%, would change the trajectory of the company.

But I don't have a formula. It requires talking to people, understanding where the leverage is, getting a feel for what's blocked and what's possible. Every company is different.

What I can say is: without this step, you're back to building data infrastructure for its own sake. The operational focus is what keeps the whole thing honest.

The architecture side is where things get tricky.

Once you've picked an operational use case, you need to think about the data model that supports it. What data sources do you need? What entities are involved? How do they connect?

Let's say you want to improve account activation. You'll have accounts as an entity. You'll have features or actions that indicate activation. Maybe you'll have a concept of milestones or success moments. These are your building blocks.

Now here's the critical question: if you build this model just for activation, and then next month you want to support another use case - say, retention analysis or expansion signals - what happens? Do you add one or two entities to extend the model? Or do you end up doubling everything because the first model was too narrow?

You're aiming for the first option. A model that grows by adding small pieces, not by multiplying them.

This requires finding the right level of abstraction. Too abstract, and the model becomes generic to the point of uselessness. You end up with one entity called "thing" that requires twenty configuration options to make sense. Nobody can work with that. Too specific, and you end up with 200 entities that only apply to one use case each. Nobody can navigate that either.

The middle ground is hard to find. Here's what helps me:

Before you build, spend one or two extra days on design. Sketch it out on a whiteboard. Then do the zoom in/zoom out exercise. Take your current model and ask: what would this look like if I zoomed out two levels? What if I zoomed in two levels? Which version would make more sense as the foundation?

This is where AI is genuinely useful. You can move through these brainstorming cycles much faster. "Show me this model more abstract." "Now more specific." "What if we merged these two entities?" It speeds up the thinking.

The test I use: if a new person joined the team, could they understand how this data setup works within a week? If yes, you're in a reasonable place. If it would take them three months just to find where all the business rules are scattered - that's a sign the architecture has grown out of control.

I've spent the last six months going deeper on this. I've made progress, but I'm not ready to publish the full approach yet. The principles are clear. The implementation details are still being refined.

So what's the takeaway?

Design-driven analytics means doing two things in parallel. You identify a high-impact operation that's worth supporting with data. And you design a data architecture that can scale beyond just that one use case.

Neither side drives alone. The operational use case keeps you honest - you're building something that connects to the business. The architecture keeps you sane - you're building something that won't collapse when the next use case arrives.

This takes two things. Experience helps - the more setups you've seen, the faster you recognize patterns. But more importantly, it takes deliberate time. Time on the whiteboard. Time sketching different models. Time asking "how can we make this simpler?" over and over again.

That's my process. It's not a framework you can download. It's a way of thinking about the problem.

Stop starting from data. Stop hoping the bridge will appear. Design it.

Join the newsletter

Get bi-weekly insights on analytics, event data, and metric frameworks.